Humility

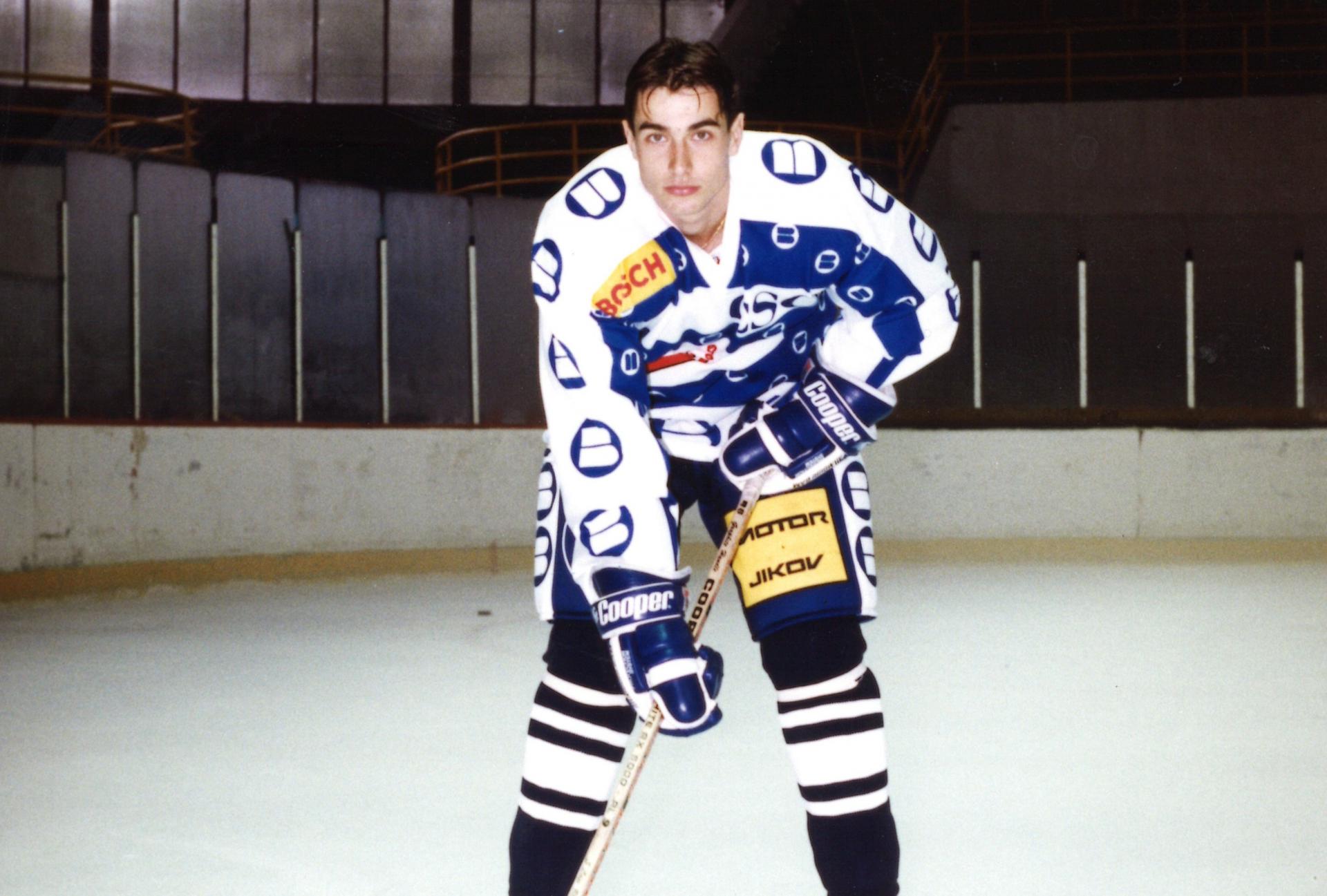

Radek Dvořák

ice hockey

The talk didn’t last more than five seconds.

Coach Jacques Martin approached me after I rejoined the Panthers and told me he had a place for me on the third line. “The first two lines are full. There are other offensive forwards. You’ll have defensive responsibilities,” he said. That was the end of the conversation.

I stared open-mouthed while my mind was buzzing with loads of questions.

So, I’ll only play shorthanded from now on? No power plays? And when 5-on-5, I’ll only go on the ice to defend the best lines of the other teams? That’s what I can do here, nothing more?

I was 30 and had just signed a two-year contract with the Panthers after playing on the first or second line for the Blues the season before. The defensive role was nothing new to me; I was trained to do this by my home team Motor České Budějovice in minor hockey. NHL coaches would often send me over the boards to play shorthanded as well. I appreciated it because I could have more time on ice. I was used to playing against the biggest stars.

However, I was still considered an offensive forward — I had some seasons with quite a lot of points. I was looking forward to having a similar role when I came back as an experienced player to a club with which I began my NHL career.

Instead, I received this blow: A blow to my ego.

You’ll be a defensive forward. Period.

I might seem like someone who gets along well with anybody and draws back only if things get complicated. But I know that I’m not like that. As with every professional athlete, I have my pride. I don’t consider myself a whipping boy who just agrees to everything. When something is beyond the pale, I stand up for myself.

Should I have done that in the situation described above? Should I have dug in my heels and said that I hadn’t joined the team only to be a defensive player?

I wasn’t sure what to do. I had to put my thoughts in order and make it clear to myself what I actually wanted; what I expected from my career.

Should I have felt sorry for myself? Should I have given up?

No, that wasn’t me. I could bite the bullet, couldn’t I?

After a few days of discontentment when I had to process this new situation in my head, I started to train with a completely new zest. I wanted to show everyone that they made a mistake by viewing me as a player whose job was to disrupt the opponent’s play instead of creating our own.

I told myself that things could change; that every cloud has a silver lining.

Above all, I approached this with humility because I still had a contract with an NHL team, and I wanted to play in the NHL until my retirement.

The humility got me all the way from the city of Tábor to the best league in the world. It accompanied me through all those years and helped me gain many lifelong friendships.

I still remember that feeling, as if it was yesterday.

The feeling after a U17 category practice when all the guys are showering and leaving home or headed to the dormitory. I take my tracksuit trousers and a hoodie and head to the opposite side of the rink with the lights already switched off.

I’m standing under the stairs, feeling the frosty smell of the ice. The rink is completely quiet, only a crackle here and there because it’s late and there’s no one coming after our practice. There’s only the gatekeeper.

Then I start running. Up and down. Up and down. Up and down. And once again.

I don’t do it to show off in front of anyone or to brag about it to the coaches. And I don’t ask the guys to accompany me. No. I'm solitary in this, and I’m doing it only for myself; just knowing that I’m working more compared to others helps me enormously. It gives me the feeling that I’m doing everything I can to be successful in ice hockey.

And I want to experience this feeling again; I’m literally looking forward to it after every practice. I’m looking forward to showering after this extra workout, knowing I did something to make my dream come true.

Even though it was hard work, of course. I didn’t really like running the stairs itself. I hated it, actually. But I believed it was a way to achieve success. And since I’m bullheaded and always want to give 100 percent when I go at something, I went running after the next practice again.

It wasn;t like I was anti-social. When the guys went for a beer after practice, I didn’t lag behind. I was a party animal just like them, no textbook example of a nice guy.

I simply arrived a bit later. After the stairs.

I was like this when I was very young, whether in school or in sports. I just wanted to do something extra; not to have remorse that I had skimped something.

Especially in hockey, I saw that it was worth it. From a certain age, you start to understand that you stand out, which drives you to become even better. In my case, the self-confidence stemmed from the fact that I used to be invited for regional select teams and later for youth and junior national teams, and that bigger Czech teams were interested in me.

First, it was Sparta Prague, when I was 14. Pavel Wohl, Sparta’s manager, offered to have me live close to their then-mainstay Petr Hrbek, who would take care of me and drive me to the rink. They would arrange a place at high school for me as well, they had it all very well thought-out.

However, I, and especially my parents, recoiled from the idea of me moving to Prague in the end. We thought it would have been too much for a 15-year-old.

So my dad went to talk to people from České Budějovice. They told him that it was nonsense to leave for Sparta as a south-Bohemian, and that they were interested in me. It didn’t take long before I signed my first contract. I started playing for Motor České Budějovice at the age of 15.

Even though I was ranked among the most talented players since I was a boy, there were plenty of better guys all around me. Unlike me, they didn’t have the same opportunities; the support from the family, for example. I could always rely on them, from my childhood to my first two years in Florida where my mom lived with me to cook and create a supportive environment.

If you want to become successful as a player — or in life in general — you need to invest a lot of effort. But you can't achieve your goals without the support of your loved ones. You need to grow up in an environment that enables you to do what you want. And even then, you still need so many things to happen at the right time.

When the crucial moment comes, some people succeed while others don’t. But from what I saw during my whole life, it’s more likely to turn out well for those who have a vision and put their heart, hard work, and humility into it. And for those with support from their loved ones, especially their family. A support that isn’t too binding. A support that doesn’t push them to skip the individual steps in their development.

In sports, it works the same as in school. You start with the first grade, then the second grade, and so on. You can’t skip and go straight to the fifth; only a few people in the world can do that.

When you devote time to something you like and have a talent for, the success will come eventually. But it’s not possible to expect it immediately and to overload the players in their childhood. Let the kids be kids, otherwise they’ll have health issues at the age of 15 instead of dealing with such complications 10 years later. They’ll be mentally worn as well.

When you push too hard, you go against the essence of ice hockey itself. The children should enjoy being on the ice.

I had never felt any pressure on me. In my whole life. I encountered it for the first time in the NHL. But at that time, I was getting paid for playing hockey, so it only made sense that I had to perform.

But as a young boy? I was simply enjoying hockey without any stress, which I think is the only way to do it.

I was crazy about hockey and I couldn’t wait for the next practice or game. Even when I got invited to play a tournament for our region’s select team, I still felt the same. I was building new friendships with guys that played against me in our league, and now we met in the same locker room. That was important. I started to realize how sport and everything connected to it really works. And how interpersonal relationships work.

How life works.

Moving to České Budějovice as a boy was a crucial moment not only for my career but for my personal development as well. Suddenly, I found myself 60 kilometres away from my family members with whom I used to spend every day at home. My dad comes from České Budějovice, so I could lean on support from my grandma and uncle, but still, it was something different than what I was used to. I had to find new friends in school and cope with the new environment. The same applied to hockey as well. Suddenly, I played with guys who had been my opponents until then, and they were the best players from the South-Bohemian region.

I was trying to find my place among them. Not because I needed to blow the doors off them feeling like I was pursuing a great career, but because I wanted to stand up to the competition.

Our coach Václav Červený used to tell us these wise words: “Guys, working hard is important. But most importantly, you have to enjoy it!”

Nowadays, many boys don’t actually know why they play hockey. This affects their attitude, thinking, and mental strength. Václav helped us understand what we wanted from hockey. At least me, because he saw my potential and guided me so that my will to work hard and accomplish something would take me in the right direction. It wasn’t as easy as it might seem now when I’m an adult. To be able to realize as a teenager why you do all of this, what’s your attitude toward hockey, toward yourself, toward life? That’s not easy at all. Therefore, it’s important to have someone who will help you realize that you do this because you love the game, and it brings you genuine joy.

Because that’s crucial.

Of course, you need to have a goal that you want to achieve. But if you don’t enjoy the journey itself, you’ll only be pursuing a void. When you get a signal at a certain age that it makes sense to pursue the journey to become a professional athlete — if that’s what you want — OK, then. Put your shoulder to the wheel and work like hell.

But again, you should do it because you see that it fulfils you, because it’ll give you a chance to make a living by doing something you enjoy. And not because you keep hearing how much the pros make and that you can earn millions of dollars.

Nowadays, it’s difficult for young players in the sense that many people see hockey as something more than a sport. Our way of living leads to commercialization, which, especially in sports, is absolutely wrong, no one can persuade me otherwise. And I know it’s up to us — our generation of guys who were lucky enough to play top-level hockey — to talk about this and to help hockey get back to its original purity so that the sport itself — the joy of being on the ice and the will to beat your opponent — is the main driving force for young boys and even girls nowadays.

Only then can you really improve. Only when you truly want it.

It’s up to us — and the active players, whom the children admire — to show what our journey was like. It’s important to have someone to look up to. At the age of 10, children don’t think about life. They just play. Who they’ll become — both as a person and as an athlete — depends on many factors. Therefore, it’s important to serve as an example.

I, for example, and many other guys from my generation (not only from České Budějovice), looked up to the legendary Motor player Jiří Lála. When I talk to him, I always tell him: “You shaped me when I was little. You don’t even know how much you helped me because I wanted to be like you.” He only smiles, but knows what I mean by that. He had his own players to look up to from the previous generations; from whom he picked up how to enjoy what you do.

Today, the boys don’t have to go to the rink to see their idols as we did. They can watch NHL players like David Pastrňák or Martin Nečas every day. It’s only natural that they look up to this environment. In my case, I started to explore the NHL only after the Velvet Revolution, when I was 12. I dreamt about playing in the NHL, but that world seemed so unbelievably distant, so I pinned my hopes on Extraliga, the highest Czech league.

I would have been happy to play even for my home team in Tábor. That’s what I had always imagined anyway. There were two teams in Tábor back then: Vodní stavby (Water Construction) who were nicknamed “Water Goblins”, and the Dukla military sports club. As children, we would watch every game of these two teams.

When I was in the fifth grade, the Swedish national team played a game in Tábor. For us, it was an incredible experience. We begged the Swedish players for some stickers, pins, or chewing gum, which resulted in an official reprimand when our teachers found out. They said it was against the idea of young socialist athletes.

My dad didn’t scold me for this. Instead, he went to see the teachers to tell them his opinion. He didn’t understand why we were punished for our love for hockey. For showing our big passion for this sport. At his intercession, the official reprimand was lowered to a warning.

Even situations like this can shape a boy’s personality; the reaction of his surroundings and how he perceives it. I saw that my parents stood up for my passion even against such a respected authority as my school.

In our family, school always came first. Even after I left for České Budějovice, focusing only on hockey and neglecting school was out of the question. My parents didn’t insist on me becoming an engineer, but I studied at a vocational school at least, although even that wasn’t easy, and I finished the last year only thanks to an individual course of study. But I had to finish it, because it’s the right thing to do at any time, especially today when studying is much easier thanks to the internet.

For a young individual, school is important because one must learn to exist in a non-sporting collective as well. Of course, every hockey player would like to be free after practices. No one really wants to do extra work. However, school teaches them to be able to sink one’s teeth in and work hard beyond the fun part.

I was 16, when I played my first game for the Motor České Budějovice A-team.

Even the practices were incredible for me — it was my first experience with senior hockey — let alone when I got the chance to play eight games during the season. The following year, I had a stable position and played with star forwards of the league, such as Luboš Rob and Roman Horák. A dream.

It sounds like a fairy tale, but it wasn’t that easy because I completely skipped one category. I was still U18 and jumped into a collective of guys who were 10 years older. It was a big change not only in terms of physical strength, but mentally as well. Overnight, I found myself among adults, and I had to cope with it. In all respects. I was gradually settling in; every day was a big experience for me.

And every experience from which you can learn something positive is beneficial. That’s what I believe.

Initially, I was worried if the old hands would accept me. I entered the locker room with players who would play for the national team at the World Championship or the Olympics, such as Radek Ťoupal, Roman “Eda” Turek, or Rudolf Suchánek, who rejoined the team the following year. I was worried that they’d consider me a child. Look at that young greenhorn, what does he want here? But they accepted me without any problems.

On the other hand, I realized that it was my duty to collect the pucks after each practice and to carry the bags for the veterans. I didn’t get butthurt. Many people might see this as a humiliation these days, but it was completely normal for us. Are you a colt? Yes. Then do it and don’t bitch about it. Nothing you could do about it, like in the military.

It wasn’t bullying, it was hierarchy. And I respected that.

When we would arrive from an away game, all the old hands would gradually get off from the bus on our way to the rink, but we — there were four of us young greenhorns — would take 20 hockey bags to the locker room and hang out all the gear before we could go home.

The old hands appreciated it. They didn’t give us a hard time. I have nice memories from that time. It taught me that if you can realize your place at a given moment, and if you don’t pretend to be something more without being too unassertive on the ice, it pays off.

This is what humbleness means for me, and I tried to live up to this all the time.

It’s true that I had to hang out the gear for the veterans at age 16, but this helped me to gain a certain position on the team. The guys accepted me without any problems and could play with me. Two years later, I found myself in the NHL with the equipment managers hanging out the gear for me.

I’m simplifying it, but it was like that in the end.

Although I was young and it was a lot for me to play for the A-team and manage everything, I wasn’t startled. I felt ready to fight for my chance. I mean, I had lived alone in a dormitory since I was 14 and I had to learn how to cope with this new environment.

I was grateful for being able to train with the A-team. It was amazing. I wanted to pursue the ice hockey player career, I wanted to fight for my chance. After some time, taking part in practices wasn’t enough for me, I wanted to play games. Then I got to taste it, and I wanted even more.

I was receiving more signals that all the work was worth it because I was getting rewarded. For example, coach Vrba put me on a line with the legendary Vladimír Caldr. He was one of the oldest players in the whole league, a true veteran, while I was among the youngest, a greenhorn. We were almost 20 years apart.

And then there was the season when Jiří Lála, my childhood idol, came to help us for the playoffs!

He was a great guy whom I watched in 1985 during the World Championship skating across the rink towards the goalie Jiří Králík, after scoring an empty-netter against Canada to celebrate the gold medal. Suddenly, I could watch his unbelievable shots during our practices with my own eyes. I saw that the rumors were true. He could hit the desired location in the net with a 10 out of 10 accuracy.

I always wondered why it was me who got this chance. Only later did I come to a reasonable conclusion. I believe that it was because I always gave 100 percent to everything. That might be the reason why I used to be the captain of regional select teams, although there were more talented guys around me. Yes, I was always one of the better players, but I definitely didn’t stand out.

But I ran the stairs after practice.

After the initial enthrallment on the A-team, I realized: “Hell yeah, I should go even harder at it“. The fact that I made it to the A-team didn’t satisfy me. On the contrary, it made me work even harder.

I had no other option. I still had the figure of a boy, and there were many things that I could improve: strength, speed, hockey sense — these were the aspects at which my teammates excelled. At the same time, I felt that it was worth working hard and improving. Not only did I want to equal my new teammates, but I also wanted to show the people who brought me to the A-team that it wasn’t a mistake, and that I could become even better.

I wanted to prove that I didn’t get into this privileged position only by chance.

I became completely addicted to it. Eventually, even the stairs after each practice felt like too little; I wanted more. I would come to the rink in the afternoon to work out in the gym in order to be better prepared for what lay ahead.

Not only did I play on a line with national team players thanks to that, I was also drafted 10th overall at the 1995 NHL Draft.

It was simply awesome. Suddenly, it was summer, and I was leaving for the US as a top-10 draft prospect.

That was the biggest challenge yet to see if I was ready. Even though I had been living without my parents and successfully integrated with a team of adult hockey players, the confidence that I gradually gained in Motor disappeared again. I was heading to something completely new. When my parents and I flew to Edmonton to attend the draft and I saw the atmosphere there, I was already sure that I wanted to try this.

However, when we were meeting with the teams where they asked me various personal questions to get to know what kind of person I was, I had to have an interpreter. The language barrier really put me through the mill at the beginning. I only learned Russian in school and opened my first English textbook when I was on the plane heading to training camp. I was toast.

Fortunately, there was a Slovak player, Róbert Švehla, one of the best European defensemen at that time, in the Panthers organization who helped me a lot. He took me under his wings. He had two children, and I basically became his third because I wasn’t even able to ask for equipment. At the beginning, he would arrange everything for me.

Here we are again. You can’t achieve anything without the support and help of the right people.

The Panthers back then were a team full of experienced Canadians. There were situations when I sat in the locker room with the others pointing at me and laughing and I didn’t know what was going on. Róbert translated everything for me, but by then, the moment had passed so I wouldn’t know how to react.

That motivated me to learn English. I wanted to show that I was not afraid to speak my mind, or to make a joke in return.

Even though my mom arrived later, I spent a lot of time calling my dad, brothers, and friends. However, there were no mobile phones at that time so I had to prepay a phone card and call from a landline. These calls helped me a lot because I didn’t have anything to do otherwise. A practice in the morning, then my extra training, but after that? I didn’t understand what they said on the TV, there was no internet, and I didn’t want to bother Róbert all the time. The first months before I learned a little bit of English were pretty tough. But I was improving when it came to hockey.

Only members of the Klub Bez frází can read further

For 199 CZK a month awaits you the plot of this and many other inspirational stories of czech athletes.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné výjimečnými sportovci, jedinečné texty od novinářských osobností plné překvapivých souvislostí, podcasty nabité informacemi a setkání s osobnostmi. Pohled na sportovní svět tak, jak ho jinde nenajdete.

Did you like the story? Please share it.