Fucking lucky guy

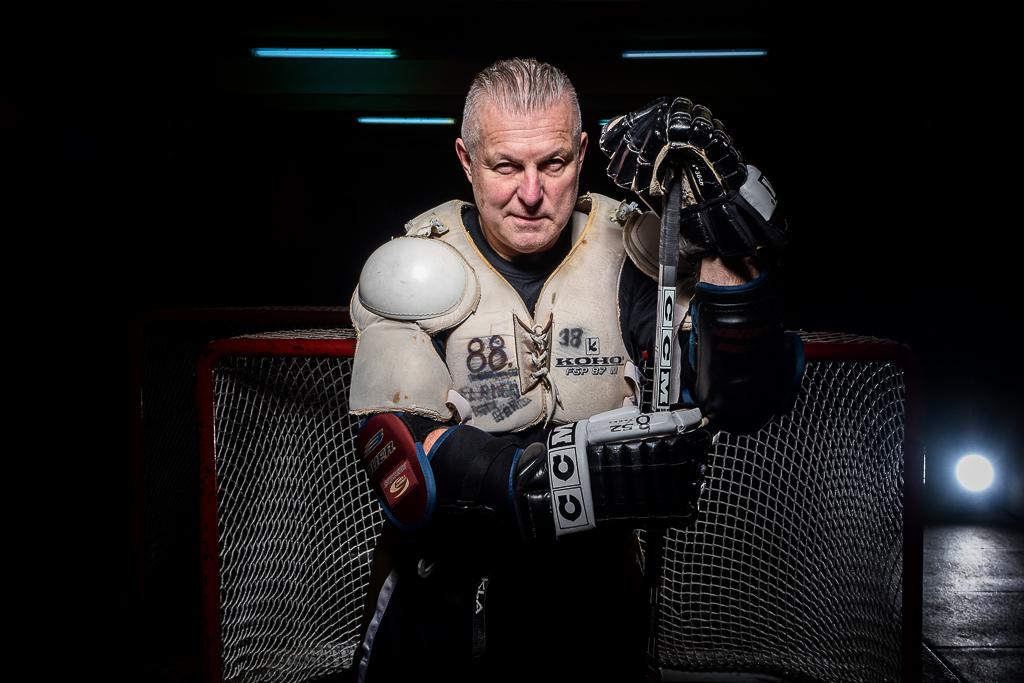

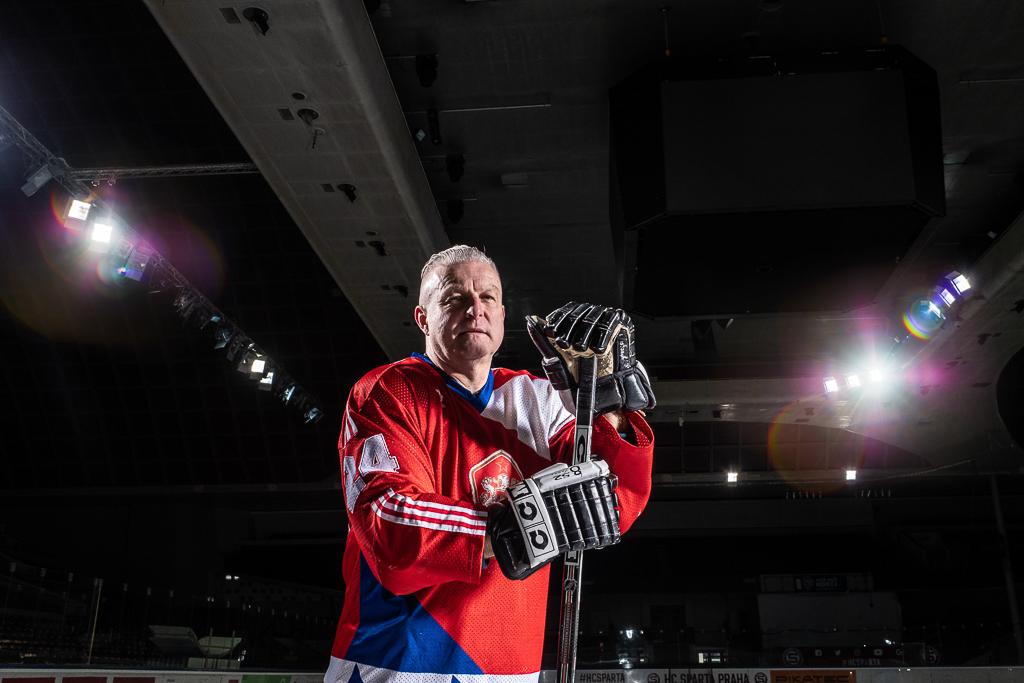

Jiří Hrdina

ice hockey

Peripherally, I noticed him coming at me. He was clearly waiting for me and he wanted to show me who the man was. That fucking European wasn’t about to prove anything in his league.

I played my first NHL game for Calgary a few days after joining the team in early March, after the 1988 Olympics. We played the Philadelphia Flyers, probably the toughest team in the league. They had Rick Tocchet, one of the most feared players, who could not only beat you up, but score goals and pass. He collected a lot of points -- he actually had a streak going at the time where he had almost 20 in five games. He was riding a wave of success and he proved it with devastating hits and even some fights. He was a guy to keep your eye on; a guy you didn't want to meet at full speed in the middle of the ice.

Now he was coming at me to take me down. I prepared and we smashed into each other, a head-on collision. I was the one who moved on. Tocchet probably figured it would be easier with me, but I was used to fighting. Although it was not so common in European hockey at the time, I did not mind the physical game. If nothing else, in every match with the Russians we tried to destroy them as much as possible, which I truly enjoyed. I always wanted to hit someone.

Tocchet ended up with a dislocated shoulder.

A moment before the hit, I had passed to Jim Peplinski for the winning goal. For that reason alone, I would consider my debut a success, but by getting the better of Tocchet, I sent a clear signal to the boys. It had an even greater impact than the assist.

When I watched the game on television, the commentators appreciated how I showed no fear. During the interviews, the journalists were also interested in how I managed to withstand the collision with such a huge man. I felt like I had attracted attention, and they immediately accepted me.

Thanks to this encounter, I always say that everything in my career was smooth. Super smooth.

I experienced a complication during my military service, when it was agreed that I would go to Jihlava, but Trenčín, despite expectations, did not take the Lukáč brothers together and reached for me instead. Otherwise, I have played an important role everywhere I have been since my youth. Things worked out for me everywhere, in Sparta and even with the national team.

When I tell someone in America today that I won three Stanley Cups in five seasons in the NHL, and only four complete ones, they laugh at me and tell me that I'm a lucky man.

"Fucking lucky guy," to be more precise.

I was a strong player who could finish and combine styles. That was me. I always wanted to play like that and I did. I quickly built up respect in our league, and because I'm also quite an emotional person, there was no shortage of situations in which it was really steaming around me. Popular among the people were, for example, my fights with Jirka Seidl from Pardubice. We went after each other in every game. I didn't avoid the places where it hurt, but I grew smarter in those situations that at first glance seem to be solely about brute force. I knew how to prepare myself when someone came after me, and I knew how to come out of a battle in the corner with a puck.

On the national team, Vladimír Růžička and Pavel Richter and I created an ideal line for the style of hockey played at the time. Pavel was an amazing technical player, Růžička was a handy center with a feel for passing and face-offs. He didn't rush into fights, but that was my strength. Together, we had a great time and I attracted the attention of NHL scouts with my style of play. Even then, teams only selected us and the Russians in the last rounds of the NHL Draft because they knew that there was a 99 percent chance we would never play for them anyway. At the beginning of the 80s, there was no indication that conditions in our country would change in any way, and the only chance to leave to play overseas was emigration.

From the Voice of America, which we listened to, of course, I learned in June 1984 that I had been chosen by the Calgary Flames, but I knew at that moment that escaping was not an option for me. I already had a family and I was scared by the idea that I might never see them again. Officially, comrades would let people abroad for merit. You had to be at least 30 and you had to have the title of world champion. When we managed to win a year later, I calculated that I would be able to go after the Olympics in 1988. I clung to that hope.

I didn't know much about the NHL. We all devoured The Hockey News, the hockey players' bible in our days. Anyone who came across them somewhere in the world brought them home. One issue circulated through countless hands. However, I only saw my first game at the premiere national team meeting in Příbram, where coach Bukač showed us a videotape of the Philadelphia Flyers playoff match.

It was an incredible game.

In the summer of 1987, everything was settled. Cliff Fletcher, the general manager of Flames, came to Prague to see me, and I left for Calgary, where, coincidentally, the Olympics were taking place, with a signed contract, knowing that I would stay. The tournament didn't work out for us, and I was glad that I didn't have to come back because the failure was portrayed at home as my fault because in my mind I was already in the NHL. It wasn't true, and those who knew me knew that when I climbed on the ice, I always did everything for victory.

While the boys were leaving, I just moved my gear through the corridors of the Saddledome to another room and then the driver took me to the hotel. There, I laid down on the bed and stared at the ceiling, my head full of thoughts because I didn’t know what awaited me.

I knew I would do my best, and at worst I would return to Europe. I made peace with this fact. Still, I was nervous as hell at my first practice. As soon as I opened the locker room door, I wondered what I was doing there. I took everyone around me as absolute pros, and I had no idea if I would ever be considered as one of them.

I did what seemed natural to me. I greeted everyone and shook their hands. Because I have always had a slightly stronger grip, I learned from the boys that they appreciated it. They felt the right amount of confidence from me.

My greeting wheel made such a positive impression that it became a ritual, and before games, I went around the room to encourage everyone.

Joey Nieuwendyk and Lanny McDonald were awesome dudes, teammates who immediately took me in. So were my new teammates from the line of Jim Peplinski and Joel Otto or Timmy Hunter. So did the Swede Håkan Loob, with whom I started living and who helped me tremendously from the beginning by explaining what the NHL was all about. But there were also those who didn't like my arrival. I felt hostility because they felt I was there to take their spot.

One week after my arrival, a young Brett Hull was traded to St. Louis.

During my first practice session, I felt terrible. All of my life, I knew only Sparta or the national team and suddenly I found myself in a completely different environment. And most importantly, I had a terrible helmet. The boys already wore modern CCMs, and the custodians prepared for me the crazy square Jofa we used to play with in Europe. I felt like an amateur in it, and after a few days I had it replaced.

Then everything progressed fast. My successful debut against Philly, my first goal in Hartford, then the next in Quebec. Of the nine games that I played by the end of the regular season, I had a point in seven of them. In addition, the boys saw that I was not a jerk and that I knew how to make fun of myself and I was not offended when, for example, they laughed at me for not understanding the exercises.

Then everything progressed fast. My successful debut against Philly, my first goal in Hartford, then the next in Quebec. Of the nine games that I played by the end of the regular season, I had a point in seven of them. In addition, the boys saw that I was not a jerk and that I knew how to make fun of myself and I was not offended when, for example, they laughed at me for not understanding the exercises.

I also knew at least a little English. Although the Canadian hockey room spoke a little differently than what I could understand after a year with my teacher in Prague, I still at least knew what was going on. The national team had traveled around the world, so I also did not stare with an open mouth in the advanced West. I had an idea of the lifestyle there, and the people from the club, even the Czechoslovak immigrants of whom there were many in Calgary, helped me with whatever I needed.

When I returned to camp before the next season, I was ready. I bought a house near the Olympic village, our girls started going to the local kindergarten and I was really successful on the ice. I scored 22 goals, had 54 points, played power plays, played on the ice at important moments. It was pure joy. At the very beginning of the season, I also managed to score my first hat trick in Los Angeles against Wayne Gretzky, the best player of all time.

I was lucky enough to play in the NHL in his era and with other greats so I could see what they could actually do. I remembered Gretzky from the U20 in the 1977-78 season, when he did what he wanted with us at the age of 16. I remembered when he came to the 1982 World Cup in Helsinki and the Canadians lived with us in a hotel. That year, he scored 92 goals for Edmonton and collected 212 points. We were all amazed by him. At every possible moment, we watched what he did and how he behaved. He was just a thin, teenage boy who sat in the lobby every night and played black jack. We didn't have the money for that, but at least we went for massages.

In the fall of 1988, I managed to score four goals against Hartford, but the Whalers were a team at the bottom of the standings. A hat trick against the Kings with Gretzky in the lineup, that was something completely different. Especially when we beat them. The 11-4 result was nothing special at that time, because such high numbers were often seen, especially with us. We didn't lose much that year and we ended up as the best team in the regular season and as one of the few in the modern history of the NHL, we continued that success in the playoffs.

For the first time, I found out how heavy the Stanley Cup was.

Yeah, fucking lucky guy, I know.

For me, however, it was primarily a huge school of overseas professionalism. Although I was one of the most productive players on the team, throughout the playoffs, I didn't even play regularly. The coach used boys whom he was convinced would help the team more at the moment. I jumped in the first round against Vancouver and then, surprisingly, in the final. In the last match in Montreal, when Joey Nieuwendyk got struck by a stick like an axe on his hand so that he could not continue, I was moved to his place and I finished on the second line.

We advanced and advanced, the mood was great and after training, when we had all worked hard, we hoped to look at the board on the wall and see our names where the coaches wrote the numbers of the players corresponding to the lines. Nobody talked to us; this was the way the lineup was announced before the game.

17… 17… 17… My seventeen was missing. So instead of playing for an hour and a half, I locked myself in the gym, often with other guys like me. We had TVs all over the room where we could watch the game, and we were lifting dumbbells or pedaling on a bike.

It was mentally difficult to stay positive. I expected the whole thing to be a little easier and was surprised. When I was just playing here and then in my first season in the playoffs, I understood it. I understood that despite my style of play, the coach probably had no idea how I would react to the intensity of the Stanley Cup matches when the referees whistled just half of what they normally whistled in the regular season. Your life was at stake in front of the net during the playoffs. I got a look at it in my first season, but the second season was harder than I would have thought.

At the same time, I was far from alone. Even players like Lanny McDonald, our captain and an absolute legend, often did not fit in the lineup. He didn't play in half of the final series before returning to the final game to score a key goal, his first and only in the playoffs. It was like a movie. Jim Peplinski and Timmy Hunter, the captain's assistants who had been part of team building for years, were also in the winning photo with the Cup in sweatpants, because they didn't make it in the four lines that day.

The NHL is ruthless like this. Even when I arrived at my first camp before this season, I was surprised that there were more than 60 of us there. Only 23 boys could make the list. I wasn't worried about my position. I thought that if they didn't want me to play on the first team, they wouldn't have taken me there. But still, I was used to the idea that whoever came into the room played.

My advantage was that as a European I brought something different to the team that the Canadian boys had not experienced so much. Loob and I were the only Europeans on the team. Later, the Russian Sergei Prjachin appeared for a short time, but in the late 80s we were still more of a rarity. Every boy from across the ocean was on the league's radar.

At that time, the difference between ours and overseas hockey was obvious. In Canada, it was automatically assumed that in a two-on-one situation, a player with the puck shoots. The goalkeeper was coming at him, the defender guarded the other without the puck. So when you faked it well, did a little shoulder move and passed, it was a beautiful goal into an empty net. The Canadians watched with open mouths.

Our teammates appreciated us, but for the opponents, we Czechs, Slovaks and Russians were always just "Fuckin’ commies," fucking communists. I couldn't even take it personally, I understood that it was part of the game. They yelled at me every game that I was just a bastard from Europe, but at the same time they knew that I would not be intimidated.

The Tocchet incident spread fast, and I kept showing that I didn't mind tough play. I also fought in the heated Battle of Alberta, as the games with Edmonton are called. However, I fought only one real fight, in Pittsburgh with a Russian from Toronto. I didn't need to prove what a tough guy I was. I wasn't there for that. In our time, there were no more brawls where whole benches jumped on the ice, they were already banned under the threat of heavy penalties. And when something went wrong and I was on the ice, I caught up with someone like Jari Kurri. We would pull our jerseys to make it look good, but we both knew that neither of us cared about fist fighting.

But that doesn't mean you didn't have to be constantly on the lookout. You did. Scott Stevens was able to shut you down, even though you didn't play on his side. His specialty was that he skated like a left back across the middle and shut you down without you knowing he was coming. He was able to eliminate opponents whenever he pleased. This is how he canceled Paul Kariya before Nagano and essentially ended Eric Lindros' career. I had the honor of playing against him at the World Championships in Prague, where in the last match he hit me so hard that I took the gold medal in the hospital.

But that doesn't mean you didn't have to be constantly on the lookout. You did. Scott Stevens was able to shut you down, even though you didn't play on his side. His specialty was that he skated like a left back across the middle and shut you down without you knowing he was coming. He was able to eliminate opponents whenever he pleased. This is how he canceled Paul Kariya before Nagano and essentially ended Eric Lindros' career. I had the honor of playing against him at the World Championships in Prague, where in the last match he hit me so hard that I took the gold medal in the hospital.

Stevens or Marty McSorley, you always had to know exactly where they were on the ice, because they were able to kill you. I take it as a success that no one ever KO’ed me, but I was badly bruised many times. As soon as you ventured through the gate, you had to count on slashes and crosschecks. No one was gentle. When I look at the game video records from my time today, because I have a few of them at home, I can’t stop staring at what was happening on the ice. It was a pure slaughterhouse, and I’m not exaggerating. I have to laugh at what is penalized in today’s NHL. The league of today cannot be compared to ours at all. I'm not saying it's good or bad — although sometimes the effort to keep the game clean is really exaggerated — it's just different. During our time, you sometimes woke up on the bench and you played the next shift.

Only members of the Klub Bez frází can read further

For 199 CZK a month awaits you the plot of this and many other inspirational stories of czech athletes.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné výjimečnými sportovci, jedinečné texty od novinářských osobností plné překvapivých souvislostí, podcasty nabité informacemi a setkání s osobnostmi. Pohled na sportovní svět tak, jak ho jinde nenajdete.

Did you like the story? Please share it.