Fight for your dream

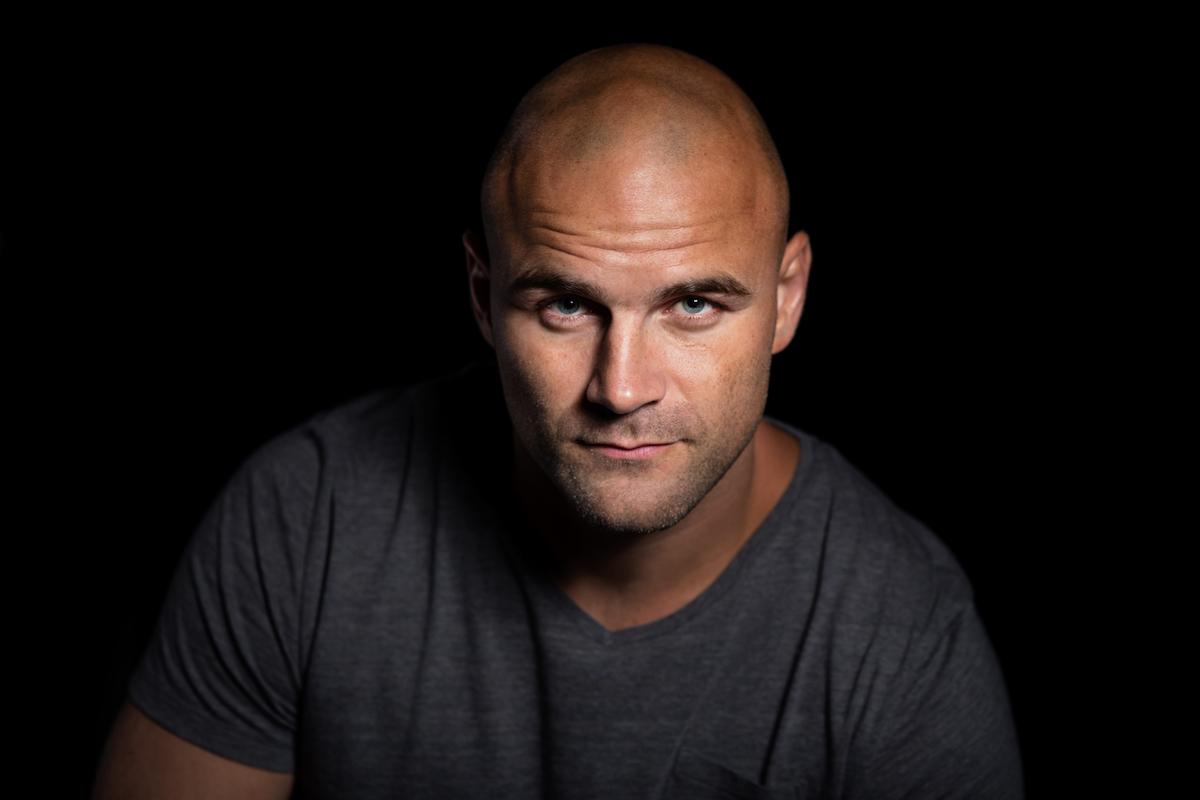

David Kočí

ice hockey

I apologize for the expression, but I can't say it any other way. In the summer of 2003, I got so fucking pissed.

The previous fall had been miserable for my hockey career in America. I was starting the second year of my rookie contract and I didn't even make Pittsburgh’s AHL team. They sent me to the ECHL, to the farm team’s farm team. When I sensed it was coming during camp, I called my agent, Mr. Henyš, and told him that I no longer saw the point in this venture. Sparta was interested in me, coach Hadamczik and I had a deal and I wanted to go back to the Czech Republic.

But Pittsburgh refused to let me go. It went so far that I asked for the number of our general manager, Craig Patrick, and I called him, this NHL icon, and told him straight out what was on my mind.

"Craig, you don’t want me here, you're sending me to the East Coast for the second year in a row, so just let me go, I don't want to be here anymore," I told him

"No," he said, curtly. That was all he said. No further comment. It caught me off guard.

"No, you will stay here," he responded to all of my other arguments. I tried to persuade him for half an hour and he didn't give me any answers other than: "No, you'll stay here."

Basically, he didn't even talk to me. When I realized that there was no other way, I hung up filled with rage. I lived in an apartment with my teammate, Michal Sivek, who had just been called up to the NHL team, and as I was raging, I swung my phone against the wall so hard that it left a pretty nice hole.

All I could do was pack up and report to Wheeling and somehow make it work. On the bright side, it was encouraging that they wanted me to stay with the club so badly, but after the season, I was really annoyed that I still hadn’t made it. The feeling bubbled inside me more and more and I poured it into training over the summer. And that’s not hyperbole. I really felt like I was working out hard, taking my stamina to a different level.

I also promised myself one more thing: When I returned to the camp, whoever touched me or gave me a bad look, I would smash him. I didn't care who it was. I realized that they liked that style in the States and I have a huge body (6-feet-6, 238 pounds), so I had all the prerequisites. I'd just try it out.

Poor Ross Lupaschuk. On the first day of the camp, during one exercise, he forced himself in front of the goal. I pushed him away and he returned it. I grabbed him and beat him up. He was an average player and I felt badly. The poor lad.

"What are you doing, are you crazy?" he shouted at me.

I didn't care, I wanted my spot. From that point, I gave everyone a beating. I knew that this was my chance, that I had to develop the aura of a madman whom everyone was afraid of. During the two preseason games in camp, no one even came close to me.

It was a game and I had found the instruction manual for it.

I made myself a loose cannon, and the coaches noticed.

I played much better than before and I jumped from the position of the 15th defenseman in the organization to almost being on the first team, all thanks to my new skill. I was sent down from the Penguins just before the start of the season; Kris Beech and I were the last ones to go to the AHL. That alone was a great honor for me.

I continued my new style of play. I whipped everyone, gaining the attention of enforcers from other teams. When I went after someone, they immediately pounced on me. I provoked them with my aggressive play, sometimes clean, sometimes to the point of being an asshole. I played pretty solid hockey and I added what people overseas call toughness: perseverance, hardness, resistance.

Next to the hockey stick, my fists became my main working tool.

Next to the hockey stick, my fists became my main working tool.

The first year felt great because you ride the euphoria wave of everyone suddenly treating you differently. Coaches, teammates and even masseurs suddenly respected you. You were no longer just a number, but a legitimate NHL prospect.

But gradually, I realized what I had gotten myself into. I'm not a natural enforcer. At first, I enjoyed the change around me, but then I realized I had to do it every day. If I stopped, they would take someone else. It's like drugs. You start to take them, you are on top and only in time do you realize that you are up to your neck in it and you can do nothing about it.

In my case, I didn't want to give up something that made me one of the top five players for my skill in the league. During that season, I ended third overall in penalty minutes. I had almost 300 of them. I competed with Brian McGrattan and Jim Vandermeer, who had more five-minute majors for fights. I had 25, they had about 30.

It was a kind of prestige. So many fights was a sign that you had no fear. In this role during our time, perhaps three goons were clearly enjoying it, the rest of us, like me, understood that this was the way we could succeed. Sometimes, I enjoyed fighting with someone, but I often knew I was going against killers like McGrattan or Steve MacIntyre, who were butchers. Before games with them, I used to feel sick, because I just knew it would be a slaughterhouse again.

But I enjoyed hockey at this level so much that I wanted to go through it.

Only members of the Klub Bez frází can read further

For 199 CZK a month awaits you the plot of this and many other inspirational stories of czech athletes.

Vstoupit do Klubu

Inspirativní příběhy vyprávěné výjimečnými sportovci, jedinečné texty od novinářských osobností plné překvapivých souvislostí, podcasty nabité informacemi a setkání s osobnostmi. Pohled na sportovní svět tak, jak ho jinde nenajdete.

Did you like the story? Please share it.